Madhur Anand is an environmental scientist at Guelph University. She is also a poet, and won a Governor General’s Award for a memoir, This Red Line Goes Straight to Your Heart.

Now she is also a novelist.

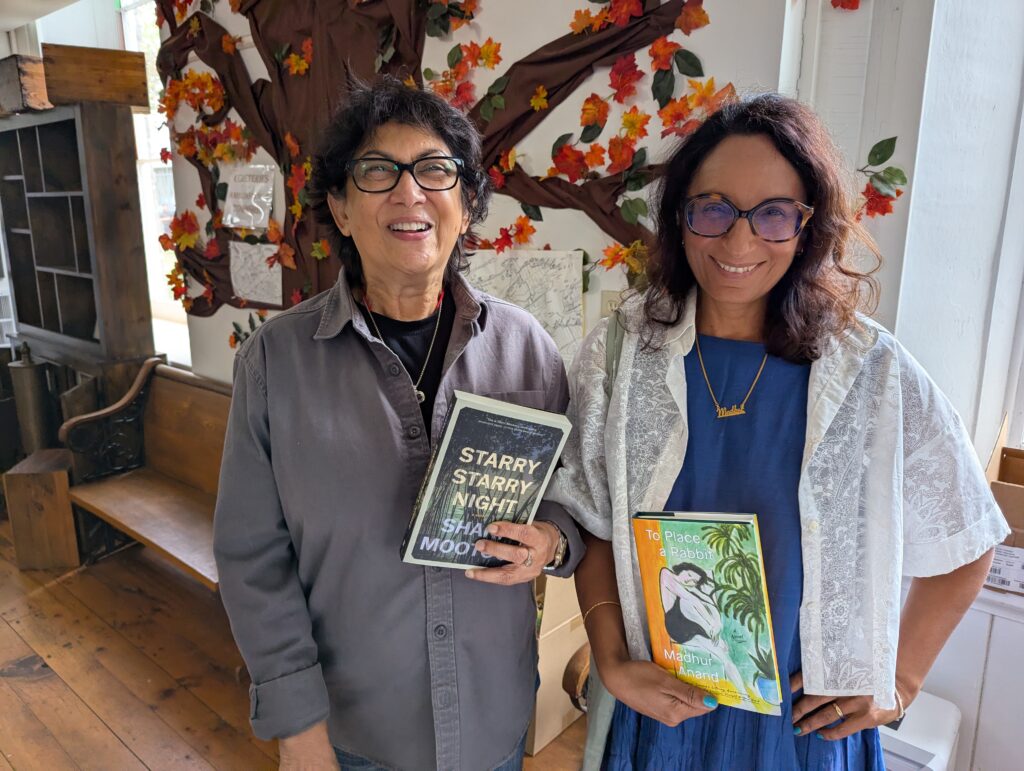

At a reading and discussion hosted by the Ameliasburgh Heritage Village last month, Ms. Anand read from To Place a Rabbit, and spoke with another award winning author, and poet, Shani Mootoo.

One of the first questions Ms. Mootoo asked was about “autofiction,” a 21st-century genre that blends an author’s own experience, or autobiography, with the conventions of the novel. Not quite magical realism, more magical memoir.

To Place a Rabbit is a first-person narrative about a scientist who wishes to become a novelist. And the way she does this is unique, drawing attention to—and questioning—the boundaries between distinct disciplines as well as between self and other, fact and fiction.

“I do share things in common with the protagonist,” agreed Ms. Anand. “I do have trouble inventing things, but I realized very quickly that this may be true for others too. As a scientist wanting to write fiction, literature, even poetry, it just feels so fictional to begin with. A scientist at a literary festival is like a character. My being there feels like a bit of little piece of theatre.”

The narrator launches herself into the literary world by proposing to translate another writer’s novel from French into English. But it is not quite so straightforward, for the French novel is, in fact, already a translation from the English. The experiment (and the idea of scientific experiment is at play throughout), is not to compare the new English to the original, but to recognize the act of translation as a creative process in and of itself.

The story is told in a set of repeating sections, Un, Deux and Trois. “It’s like a waltz,” suggested Ms. Anand. Un narrates the near present of the scientist attending literary conferences and working on the translation. Deux offers passages from the “translation.” Trois delivers a more distant past in which the narrator remembers a failed love affair which took place in French. Echoes connect the sections, culminating in the final section, Ménage à Trois.

The novel begins from a position of scientific doubt and distance. The scientist narrator has little affect as she tells her story. She cannot understand why people ask questions about her book, “all the answers were in my book, but even so, people asked them.” She is reserved and analytic: “I moved toward two men in conversation, who generously met my gaze and smiled to invite me into their space. We stood in a triangle.” This affective detachment can be alienating to a reader who expects more showing and less telling.

We come to realize, though, that the narrator is alienated from herself. The book presents a hall-of-mirrors; one of its favourite terms is “mise en abyme,” an endless series of representations within representations.

The displacements of the self through translation ultimately result in coincidences in the narrator’s world which suggest that fiction and reality are not so far apart, and may in fact overlap. By the end of the story, as Ms. Mootoo noted, a passion has taken over. “The protagonist begins to become undone and raw emotion, painful truths, contradictory desires unfold. One gets a sense by the end of the book that fiction has to be more reliable than science because the emotion was so strong and powerful and overtaking.”

Ms. Anand’s appearance came of a residency at the Al Purdy A-Frame. She will be returning to the County to participate in the launch of the Al Purdy A-Frame Alumni Chapbook at the Picton Public Library on October 4.

Ms. Mootoo will be at the Picton library, in a conversation with Carlyn Moulton to launch her new novel, Starry Starry Night, the story of a young girl growing up in Trinidad, on October 1.

See it in the newspaper